“There is a point at which, if only one more person tunes in to a new awareness, a field is strengthened so that this awareness is picked up by almost everyone.”

— Ken Keyes Jr., The Hundredth Monkey

In the 1950s, researchers studying Japanese snow monkeys on Koshima Island made a discovery that became the foundation of the now-famous Hundredth Monkey story. Popularized by Ken Keyes Jr., this story has inspired activists, organizers, and those fighting for social change. Although science suggests a more gradual process, the lesson stays clear: new ideas can spread rapidly through community connection — and this insight offers powerful lessons for anyone preparing for a general strike or building a mutual aid network.

During their study, the researchers used sweet potatoes that the monkeys were foraging for to create a connection with the monkeys. The scientist observed something unusual: one young monkey, Imo, learned to wash her sweet potatoes to remove the sand. This simple act spread—first to her mother, then her playmates, and eventually to many of the younger monkeys in the troop.

Ken Keyes Jr. used this as a powerful metaphor in the forward of his book The Hundredth Monkey. (The original text from the book is posted at the end of this article.) He described a moment when the 100th monkey learned this new behavior, and suddenly, the entire population began doing it. The idea was captivating: that once a “critical mass” adopts a new thought or behavior, change spreads rapidly, even telepathically across oceans.

It’s a hopeful story. But how true is it?

What Science Really Shows

Keyes’ story “supposes” details, imagining the 100th monkey was a catalyst for social change, but scientists and their research reports are thorough. Unfortunately, the research does not support the “ideological breakthrough” phenomenon in the miraculous way Keyes describes.

In 1958, 15 out of 19 young monkeys and 2 out of 11 adults were washing sweet potatoes. By 1959, washing sweet potatoes had become a common behavior for the group. By January 1962, nearly all the monkeys in the troop, except those born before 1950, were observed washing their sweet potatoes.

This new behavior gradually spread through relationships, especially among younger monkeys and their families. Most older males, who had limited contact with the young, never adopted this behavior. There was no magical 100th monkey, no spontaneous mind-to-mind transfer. The behavior may have jumped from one island to another, but so did the scientist, and well, monkey see, monkey do.

But that doesn’t diminish the story’s power.

The key point remains transformative: new behaviors begin small, expand through connection, and eventually become an integral part of the culture.

What the Hundredth Monkey Teaches Us About the General Strike

In a society plagued by economic injustice and corporate dominance, we often look for that “breakthrough moment,” a viral act of resistance, a critical mass that creates a tipping point and instantly changes everything.

But breakthrough moments of social change do not happen in a vacuum.

Change starts with you. One person choosing to prepare, speak up, and organize. That action ripples out to a friend, a neighbor, a coworker, and suddenly, something bigger begins to take shape.

Like the spread of sweet potato washing among monkeys, grassroots movements and labor strikes grow through solidarity and everyday interaction. A general strike won’t happen by magic or a sudden mass awakening; it starts when people discuss it in kitchens, break rooms, and mutual aid networks. Just as older monkeys learn from younger ones, we can pass down strategies for economic resistance, workplace organizing, and community resilience.

The Real Moral?

You don’t need to change the world overnight. Just do something different today and share it. One new behavior. One refusal to comply. One act of mutual aid. That’s how movements grow. Not with fanfare, but with footsteps.

If you’ve ever wondered how to join a general strike or what it takes to prepare, now is the time to start. Small acts add up — one flyer shared, one coworker convinced, one act of mutual aid.

Are you ready to start?

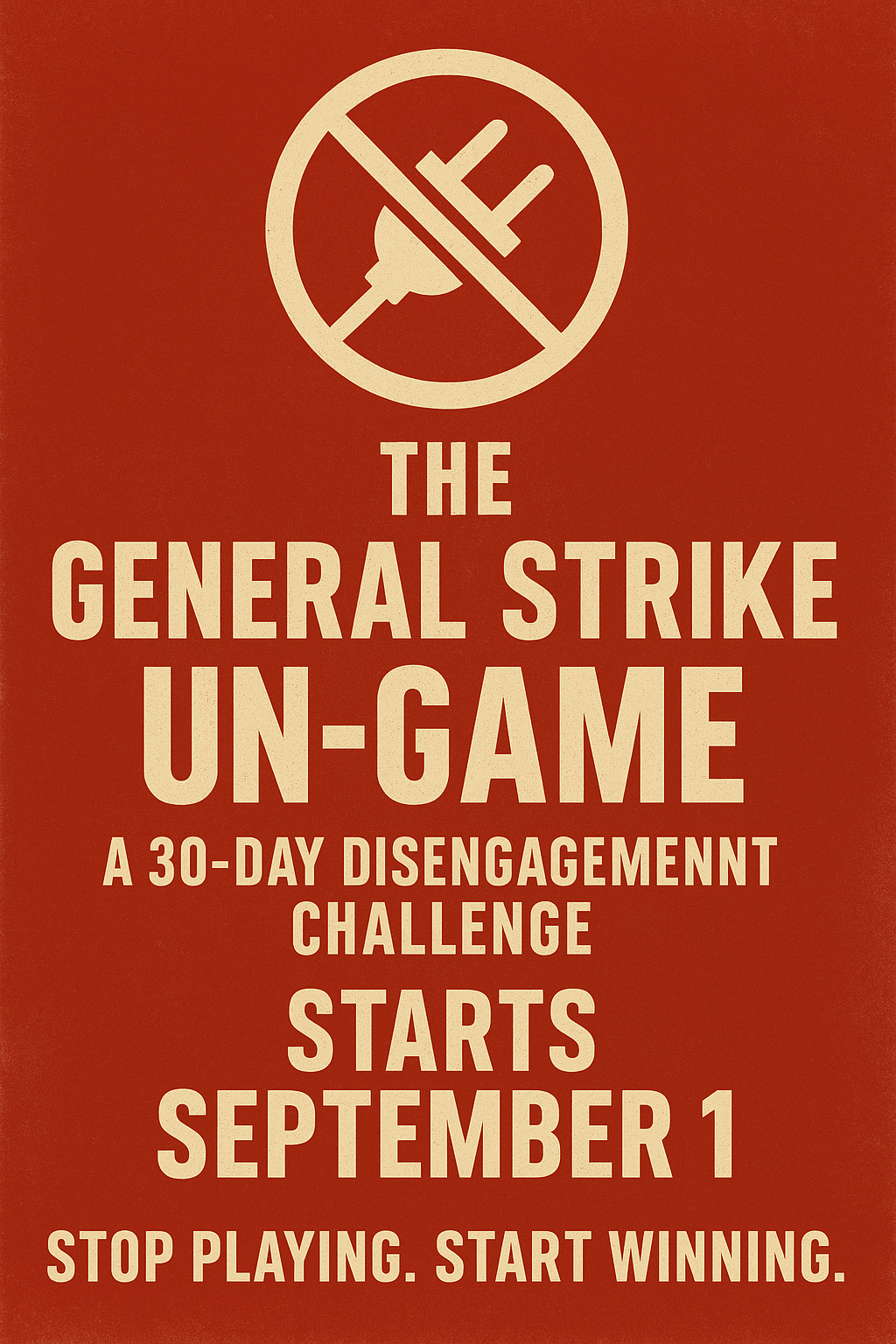

[Download the General Strike Survival Guide] to learn proven strike preparation strategies, connect with mutual aid networks, and see how grassroots organizing creates real change.

The truth about the Hundredth Monkey story is that change comes from persistence, not magic. Whether you’re seeking everyday activism ideas or aiming to participate in large-scale collective action, your role is important. Be the hundredth monkey. Stand with workers. Help build the momentum toward a general strike that challenges economic injustice and creates a future rooted in solidarity.

Let’s stop pretending this is normal.

You’re not alone anymore.

Let’s get started now.

_______________________________

The “Hundredth Monkey” story is presented here as a metaphor for how ideas and behaviors can spread through communities. While inspired by real observations of Japanese macaques, the concept of a sudden “tipping point” or telepathic transfer of behavior is not supported by scientific evidence.

The Japanese snow monkey had been observed in the wild for a period of over 30 years.

In 1952, on the island of Koshima, scientists were providing monkeys with sweet potatoes dropped in the sand. The monkey liked the taste of the raw sweet potatoes, but they found the dirt unpleasant.

An 18-month-old female named Imo found she could solve the problem by washing the potatoes in a nearby stream. She taught this trick to her mother. Her playmates also learned this new way and they taught their mothers too.

Various monkeys gradually picked up this cultural innovation. Between 1952 and 1958 all the young monkeys learned to wash the sandy sweet potatoes to make them more palatable. Only the adults who imitated their children learned this social improvement. Other adults kept eating the dirty sweet potatoes.

Then something startling took place. In the autumn of 1958, a certain number of Koshima monkeys were washing sweet potatoes — the exact number is not known. Let us suppose that when the sun rose one morning there were 99 monkeys on Koshima Island who had learned to wash their sweet potatoes. Let’s further suppose that later that morning, the hundredth monkey learned to wash potatoes.

THEN IT HAPPENED! By that evening almost everyone in the tribe was washing sweet potatoes before eating them. The added energy of this hundredth monkey somehow created an ideological breakthrough!

But notice: A most surprising thing observed by these scientists was that the habit of washing sweet potatoes then jumped over the sea…Colonies of monkeys on other islands and the mainland troop of monkeys at Takasakiyama began washing their sweet potatoes.

Thus, when a certain critical number achieves an awareness, this new awareness may be communicated from mind to mind. Although the exact number may vary, this Hundredth Monkey Phenomenon means that when only a limited number of people know of a new way, it may remain the conscious property of these people.

But there is a point at which if only one more person tunes-in to a new awareness, a field is strengthened so that this awareness is picked up by almost everyone!

_______________________________

The information provided on this website is for educational and informational purposes only. This information is not intended to be taken as legal, medical, or professional advice. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the company or its affiliates. Visitors are encouraged to conduct further research and consult with relevant professionals.

No products in the cart.

No products in the cart.